Beyond the Headlines

In a recent article by The Toronto Star, the spotlight was cast on the ownership dynamics of Toronto's new condos, sparking heated debates and raising eyebrows. However, as we dive into the intricacies of this matter, it becomes clear that the narrative might be missing some crucial details.

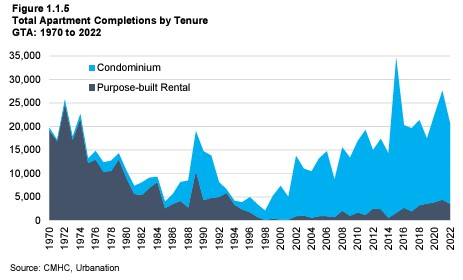

The article suggests that investors owning more than 50 per cent of Toronto's new condos is a cause for concern, leaving many scratching their heads. But here's the reality check – this isn't a new phenomenon. Toronto has danced with this housing tango for decades, with the only change being the type of housing in the limelight.

A Trip Down Memory Lane

Back in the '70s, purpose-built rental buildings were the of the show. Corporations and developers crafted apartments for eager residents.

Fast forward to today, and the script has evolved. Condo developers have taken center stage, and the supporting actors are mom-and-pop investors, turning these condos into rental units.

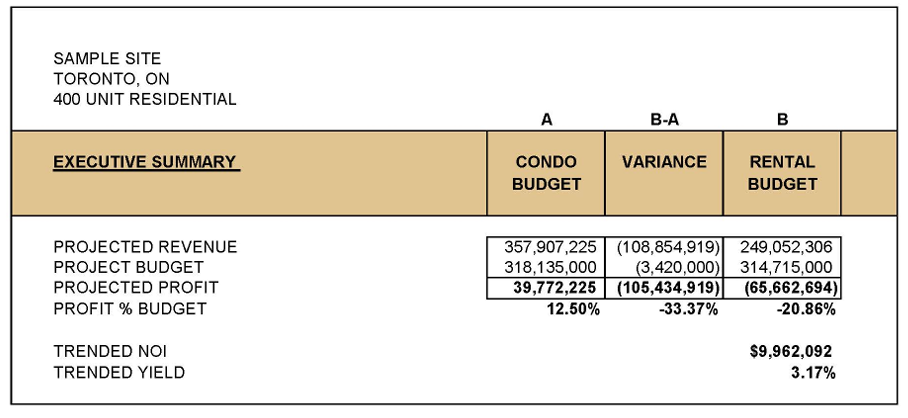

To elucidate the challenges contributing to the scarcity of purpose-built rental (PBR) developments in the region and the consequent lower percentage of PBR in the housing stock, BILD and FRPO enlisted the services of Finnegan Marshall, a multidisciplinary real estate and development cost consulting company. In January 2023, Finnegan Marshall conducted two pro forma financial analyses for a hypothetical 400-unit residential development, examining it first as a condominium and then as a purpose-built rental to evaluate their relative financial viability.

The high-level results for Toronto's pro forma offer a budget estimate for completing a 400-unit condominium development in downtown Toronto and a 400-unit purpose-built rental development, encompassing the first year of operations. The one-year operating period for the rental pro forma aligns with the condominium project, facilitating a like-to-like comparison. Both analyses include all associated project costs, from land acquisition and planning to fees, taxes, and construction.

For the condominium project, the total cost for development, construction, marketing, selling, legal, and professional fees is $318,135,000. Projected revenue from selling the 400 units at $1,500 per square foot totals $357,907,225, resulting in a profit of $39,772,225 or 12.50% of project costs.

In contrast, the purpose-built rental project involves a cost of $314,715,000 for development, construction, rental operations, legal and professional fees, along with operating costs and maintenance for the first year. Projected annual revenue is $14,650,136, based on an average monthly rent per unit of $2,869, plus associated locker and parking stall rentals.

After deducting annual operating costs of $4,688,043, the project yields a net operating income of $9,962,092. However, following the first year of operation, the project experiences a deficit of $65,662,694 compared to the budget for building and operating, requiring over seven years to reach breakeven.

So, why the uproar now? It seems the narrative has shifted from corporations profiting off massive apartment complexes to pointing fingers at a new scapegoat, mom-and-pop investors. The truth? Investors, whether corporate or familial, have always been part of Toronto's housing landscape.

The term "speculator" is thrown around like confetti, with suggestions of an 80 per cent capital gains tax on appreciated values. However, the humor in this situation isn't lost – condos today are apparently in negative cash flow territory, a stark contrast to the prosperous image painted.

Taxing Success in True Canadian Fashion

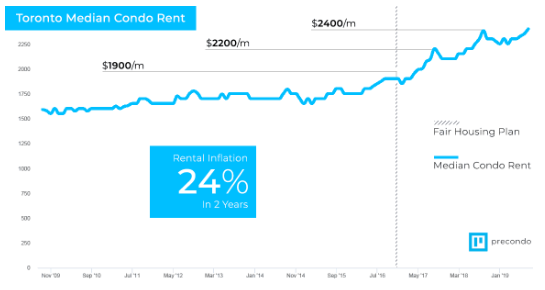

A tongue-in-cheek observation points out Canada's penchant for taxing those who are doing well. The article draws parallels to the consequences of deterring investment, harking back to the days when rent control was rolled out in Ontario. The aftermath of the Fair Housing Plan introduced by the provincial Liberal government headed by Kathleen Wynne at the time? Toronto condo rents inflated by a staggering 24 per cent over two years.

Correlation or Coincidence?

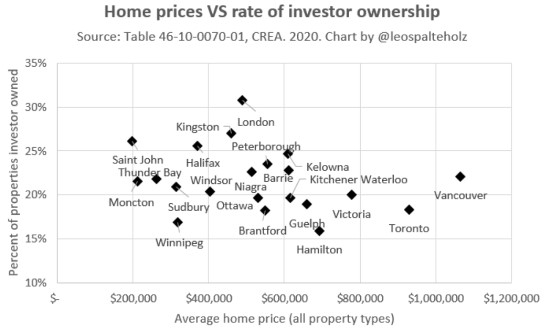

The article delves into the correlation (or lack thereof) between investor ownership rates and average home prices in various Canadian cities. Surprisingly, there's no clear connection.

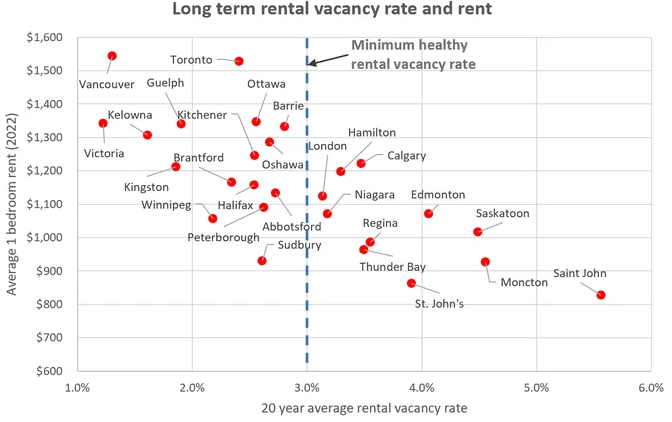

However, when you switch the lens to vacancy rates versus average rent prices, the picture sharpens.

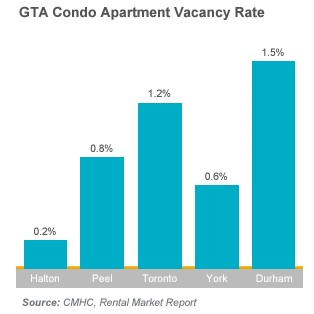

According to the Rental Market Report produced by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) in January of this year, Toronto, among the three largest markets in the nation, showed the most significant disparity in rent growth between units that experienced turnover and units without turnover.

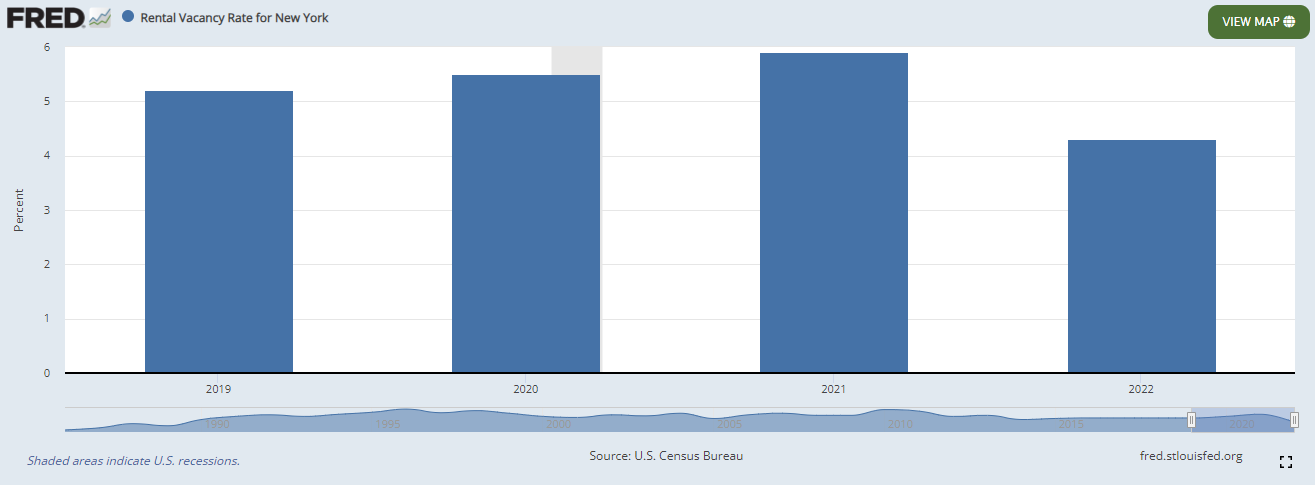

Moreover, Toronto's abysmally low vacancy rate of 1.2 per cent is causing rent prices to skyrocket, a stark contrast to New York's healthier 4.3% vacancy rate.

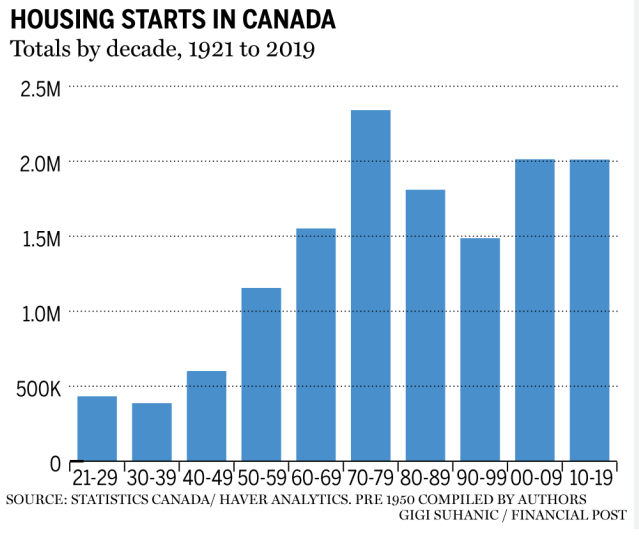

Toronto's low vacancy rate unveils a deeper issue – a shortage of homes. In the 1970s, Canada experienced its golden era of home building, constructing over 2.3 million homes. Fast forward to today, and we find ourselves in a housing shortage predicament.

There are structural and intellectual deficits affecting new housing construction. Structural deficits include challenges related to land availability, labor, and capital. They note that much of the urban and peri-urban land has already been developed, and obstacles like Not In My Back Yard (NIMBY) sentiments and environmental concerns hinder further construction.

The intellectual deficit, according to Murtaza Haider, professor of real estate management and director of the Urban Analytics Institute at Toronto Metropolitan University, is surprising. He argues that a negative perception of new development and the demonization of investors and developers hinder progress. He specifically highlights a campaign against investors in housing markets, emphasizing the importance of their role. The article suggests that limiting or eliminating investors' involvement could have catastrophic consequences, especially for vulnerable cohorts like renters.

The author explains that almost 100 per cent of renters live in dwellings owned by investors, whether individual or corporate. They attribute the decline in purpose-built rental (PBR) housing construction to changes in tax laws since the 1970s. With a significant portion of renters living in non-PBR apartments, the role of housing investors becomes crucial in maintaining the rental housing stock in Canada.

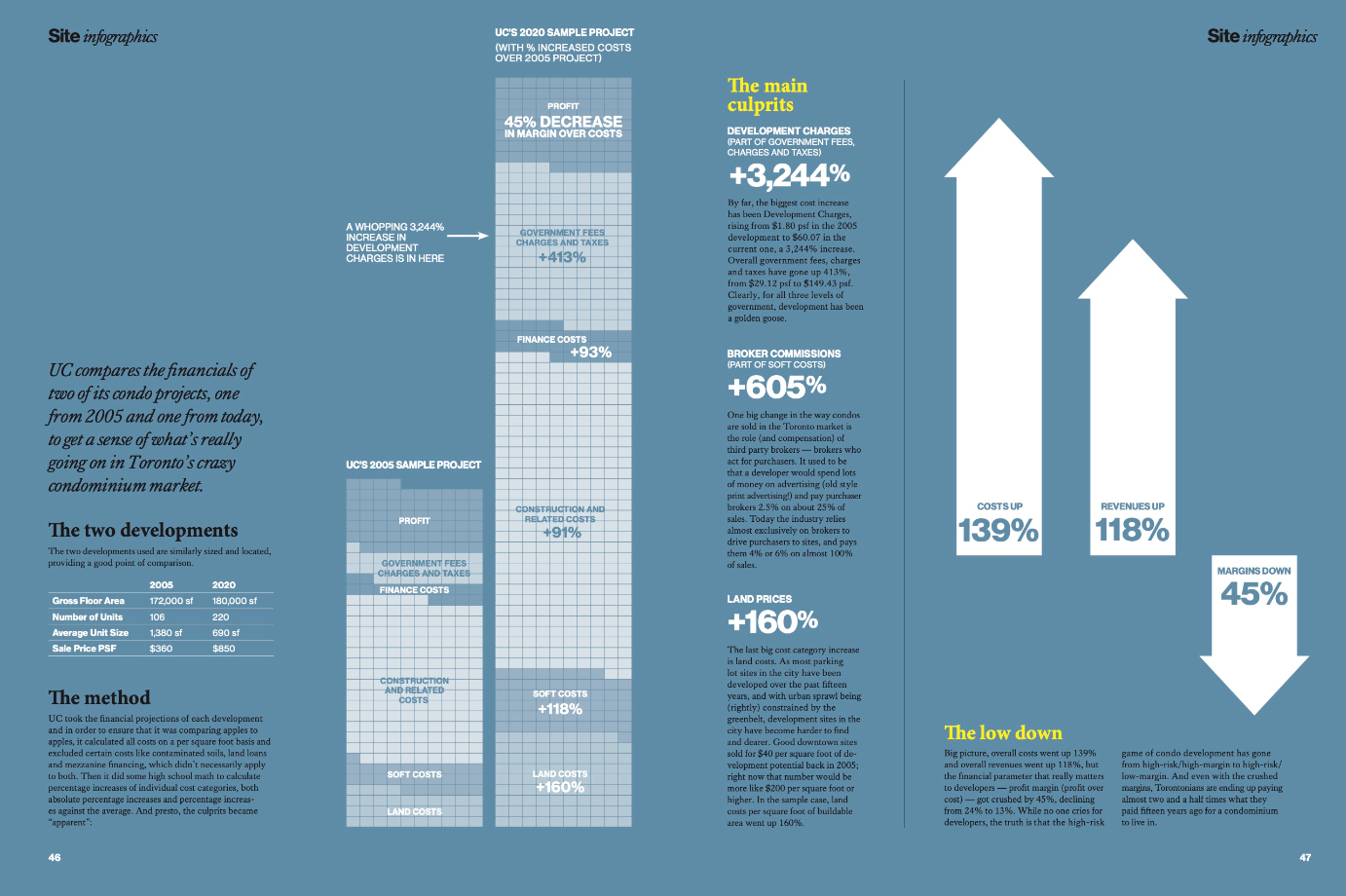

From 2005 to 2020, the statistics paint a daunting picture: a 150 per cent increase in average condo prices, a 160 per cent surge in land costs, and noteworthy upticks in soft costs, construction-related expenses, and financing costs. However, the most concerning aspect is the 413 per cent spike in government fees, charges, and taxes, with development charges experiencing an astronomical surge of 3,244 per cent.

This surge in development charges has cast a shadow over new housing projects, making them significantly more expensive and posing a substantial hindrance to new development. Consequently, developers are grappling with a delicate balance, forced to accept rising costs, including these exorbitant development charges, leading to a continuous upward pressure on end prices.

The decline of profit margins by 45 per cent underscores the formidable challenges developers face in navigating this complex real estate landscape, emphasizing the need for a nuanced approach to address the negative impact of soaring development charges on new housing affordability and overall development prospects.

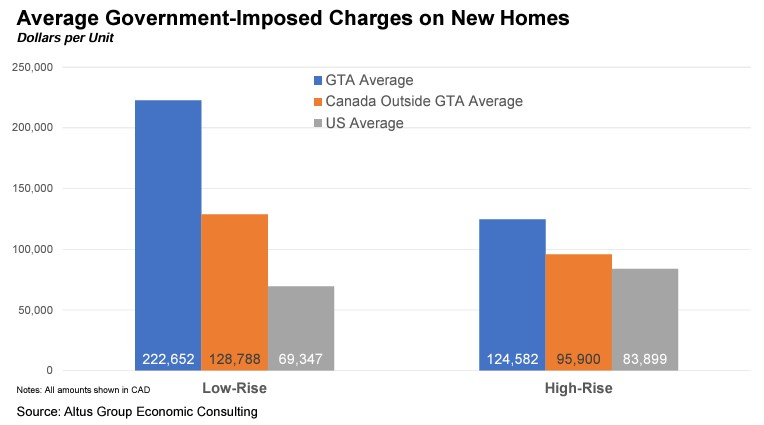

The average per-unit government charges for high-rise developments in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) are approximately 50 per cent higher than those in six surveyed US metropolitan areas and roughly 30 per cent higher than in other Canadian urban areas. When expressed as a percentage of new housing prices, the charges for new homes in the GTA (ranging from 19.4 per cent to 20.7 per cent) significantly surpass those in other Canadian urban areas (14.9 per cent to 15.9 per cent) and the US metro areas (6.5 per cent to 8.2 per cent).

One major factor contributing to the lower charges in US metro areas is the absence of sales taxes on new housing, whereas in Canada, sales taxes on new homes range from 5 per cent to almost 15 per cent, impacting the overall government charges.

For developer-incurred government charges, when expressed as a percentage of new housing prices, the GTA again stands out with charges between 8.6 per cent and 10.8 per cent, compared to other Canadian urban areas (4.6 per cent to 4.7 per cent) and US metro areas (4.4 per cent to 6.2 per cent). The primary reason for higher developer-incurred charges in the GTA seems to be the substantial development charge costs imposed on new homes, reaching nearly $100,000 per unit in some jurisdictions, constituting 68 per cent to 82 per cent of developer-incurred charges for high-rise and low-rise development, respectively.

The comparison below illustrates the estimated government charges on new housing in six US metro areas versus various Canadian cities, both within the GTA and elsewhere in Canada.

The charges in Canadian cities outside the GTA significantly exceed those in almost all US metro areas. Specifically, the charges per low-rise unit in the GTA ($222,700 or $89 per square foot) are over three times higher than the US average ($69,400 when converted to Canadian dollars or $28 per square foot). Even for high-rise units, the average charges in the GTA (approximately $124,600 per unit) surpass the average charges in the six US metro areas, which amount to roughly $83,900 (in Canadian dollars). In terms of a percentage of typical housing prices, the average GTA charges represent 19.4 per cent, compared to 6.5 per cent in the US metro areas.

So, what's the takeaway from this rollercoaster of housing revelations? Toronto's condo conundrum is not a crisis born overnight. It's a symphony of historical patterns, investor adaptations, and governmental decisions.

Before joining the bandwagon of criticism, it's essential to understand the dynamics at play. Investors, be they mom-and-poop investors or a faceless corporation, are not inherently villains. They're navigating a market shaped by decades of evolution.

Let's not forget that solutions lie not in finger-pointing, but in thoughtful analyses, collaborative efforts, and perhaps a sprinkle of humor to ease the tension in the housing narrative.

Your market

Curious where our market falls on this split and what it means for you?

Get in touch, and we’ll tell you everything you need to know.